As we enter the third of year of a pandemic, we continue to search for solace, peace, and balance in our everyday life. It’s never been more evident that the design of our environment is vitally important. It affects how we use the space we inhabit, and what we can or cannot do. In the past two years, we have all become keenly aware of how the design of our environment affects our ability to social-distance and abide by our government’s public health guidance. It has become a major point of discussion for planners, designers, and builders. However, prior to 2020, designers have always had to and continue to face a multitude of pressing issues. From ecological sustainability to climate change, and social needs for parks and open space in our ever-densifying downtown cores, landscape architects tackle our most challenging design dilemmas today.

It is a daunting task to address everything from ecology, climate change, safety, security, resolving issues and creating inventive solutions to site challenges that are often in conflict with existing and proposed structures, and it is the job of landscape architects to provide solutions to these complex issues. Balancing all these issues while creating a beautiful, functional landscape is no small feat. Solving the many site challenges a project will inevitably encounter all while creating a lasting impression that will stand out as a memorable landscape requires something more. That is why moving forward, we, as landscape architects, must focus on project designs that are relatable; something that the user or visitor can understand and experience. As landscape architects it is our goal to tell a story through our designs that will connect the audience to one’s place and context. We believe in the importance and the power of storytelling through landscape architecture. By communicating important and timely stories through design concepts that evoke notions of history, nature, and the universe, we begin to transcend spatial design to one that is steeped in meaning and timelessness.

At 240 Markland Drive, a proposed condo building that will be located east and north of an existing residential tower. With this arrangement, a new arrival court will be located in the center of the development. While taking inspiration from a unique existing building condition, an open-air ground floor space suggested a possible approach of creating what we called “landscape porosity”.

The goal will be to continue the existing visually porous nature of the site and apply it to newly proposed landscape and architectural elements so that one can truly see and feel the free-flowing landscape treatment that will integrate the existing and proposed building sites.

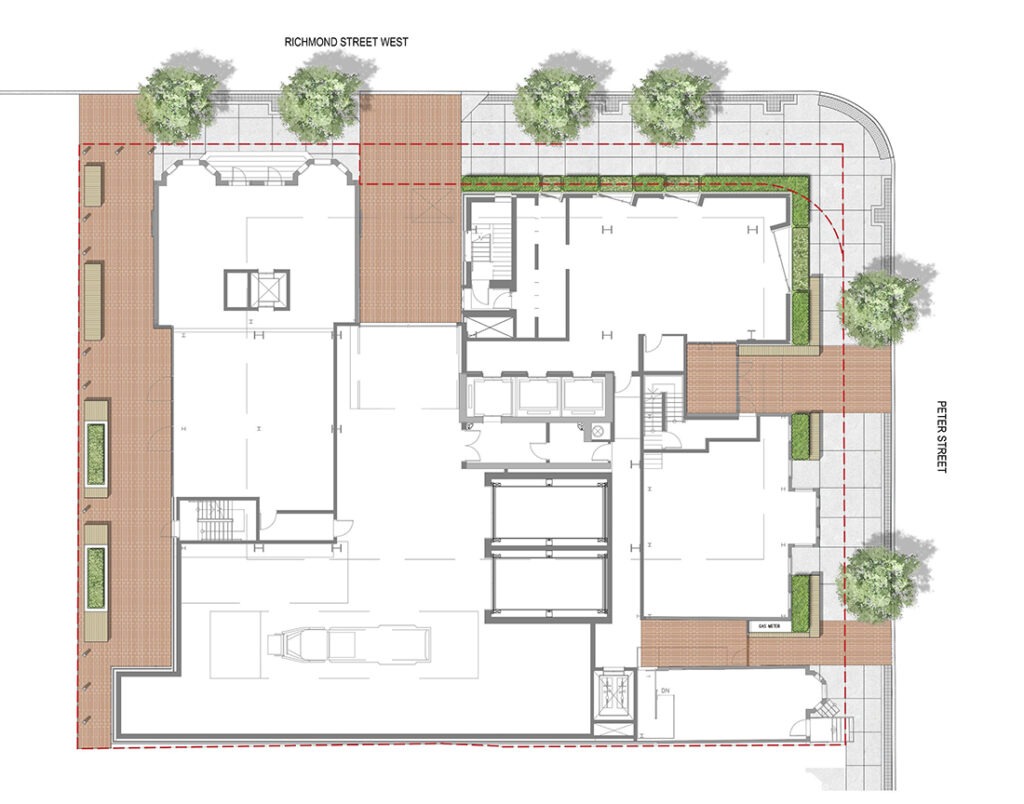

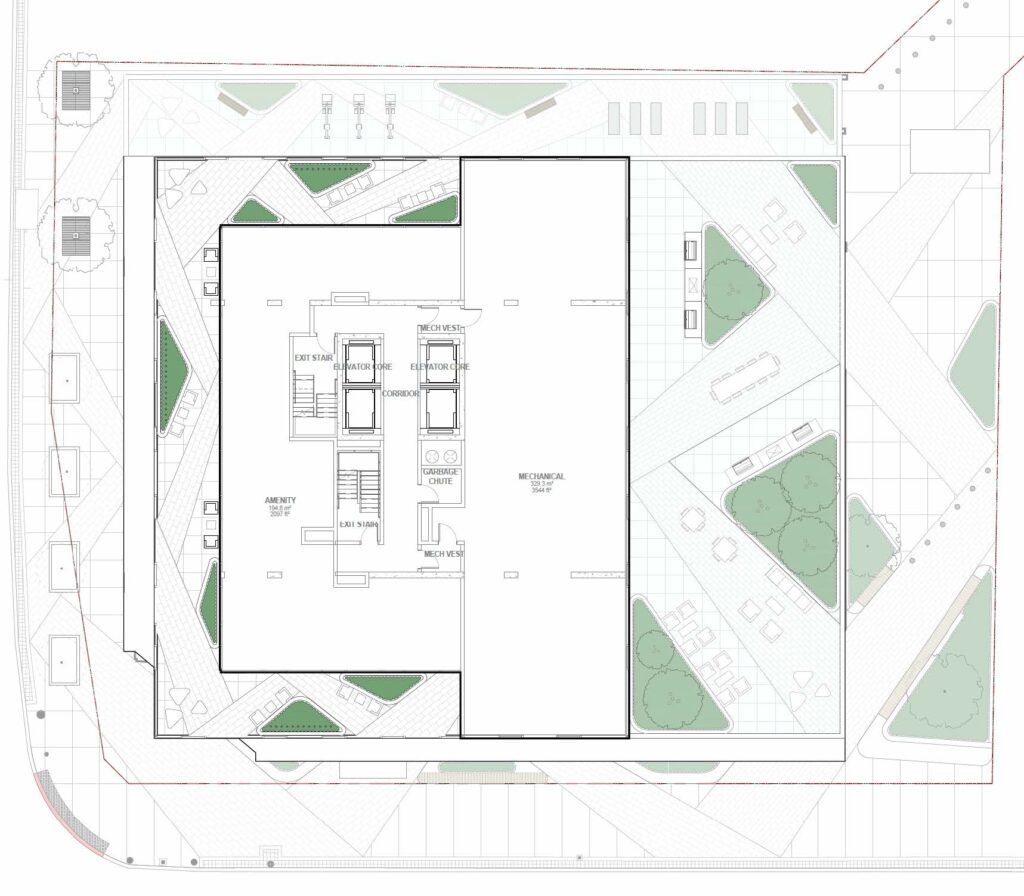

At the corner of Peter and Richmond Street West, sit three heritage buildings from different periods in the historic Fashion District of Toronto. Both structurally challenging and visually stunning, a residential tower will rise above, and the landscape design will explore the notion of “heritage landscape”.

With the heritage buildings preserved, a new, yet old and ‘heritage’ in appearance landscape treatment will be created with brick paving and corten steel elements. This ground floor modern heritage treatment will also be applied to the multi levels of roof amenity space – to challenge the notion of heritage that is old, can also be new.

A landmark location in the city, demands a landmark and unique landscape approach. A 37 floor residential tower will be located at the northern axial view terminus of Spadina Avenue that will be as significant as the current One Spadina Crescent (Daniels Building). In order to relate and visually connect the amenity roof levels to the ground floor and proposed POPs (Privately-Owned Public Space), a 3-dimensional “landscape ribbon” was proposed to wrap the building through its unique structural columns and landscape paving bands and planters.

This talk is an excerpt from Terence Lee’s talk at the University of Guelph.